Assumptions on cost calculations

One has no idea what long term future inflation and productivity gains will be, so unit costs are based on current (Earth) prices and costs unless there are specific reasons otherwise, as is the case with water.

A key assumption is that if the habitat is in deep space a strong magnetic field is generated around each cylinder to deflect solar wind and cosmic rays. The water jacket and plastic shell assumed are secondary protection, similar to the absorptive role of the atmosphere on Earth. If the habitat is in Low Earth Orbit, no magnetic field would be required. I have made some assumptions below for the construction of the shell, although it may (probably would) work out a bit different in practice. The shell would need to balance the following:

- minimising cost

- radiation protection

- corrosion resistance, to exposure to both water and air

- enough tensile strength to support at least two storey buildings, with the added stress of the centrifugal force from the rotation of the habitat

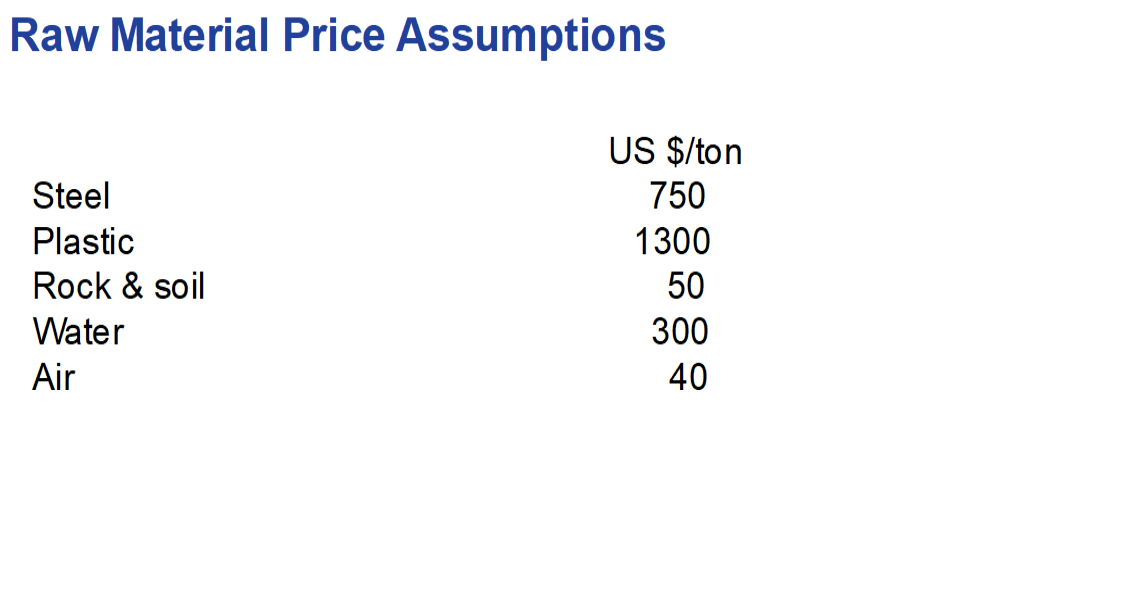

Steel: 10mm plate for the outer shell. It is assumed to be sourced from M type near earth asteroids where the metal does not need smelting from ore but processing costs to steel plate may be higher than on Earth, and a corrosion resistant coating due to contact with water jacket. For the annular cylinder model, I have also assumed steel for the “roof” shell, as it is the cheapest option. This needs to be airtight, but otherwise no structural load or radiation protection (it is entirely inside the cylinder) so have assumed 5mm plate (typical hot rolled steel sheet is 2-3mm gauge). On average I have assumed $750/ton for steel, 50% higher than a current Earth price.

Plastic: 20mm plate assumed for inner shell, pretty robust but it has to bear the weight of at least two storey buildings. For radiation protection and modest cost, high density polythene is ideal, but it does not have high tensile strength or resistance to surface wear and tear. So I have assumed a coating of sintered asteroid rock, and probably a supporting steel frame. So a relatively high cost of $1300/ton is assumed (current HDPE prices on Earth around $900/ton).

Water: a 30cm jacket between outer and inner shells (radiation protection) another 10% for other uses such as ponds and for consumption in industrial uses. The cost of $300/ton is high as part of it probably needs to be sourced and transported from Ceres. It may be cheaper processed from asteroid mining, but as previously mentioned the volumes of water available may be rather limited. Water turns out to be the biggest cost element.

Soil: A by product of asteroid mining, which would otherwise be dumped and so cause environmental issues (more potential space junk). So a fairly nominal price of $50/ton assumed. If most agriculture is hydroponic not much is needed, 20cms coverage throughout the habitat assumed for costing, in practice it would be more unevenly distributed.

Air: I have assumed 80% of sea level air pressure on Earth ( that is, 0.8 bar) which is like living at 2000 metres altitude, which doesn’t cause people problems (at the 4000m height of Tibet or the Bolivian altiplano it is only 60% of sea level, yet that does cause altitude sickness). Cheap ($40/ton), collected by skimming through the Earth’s atmosphere.

Then there is the cost of assembling the habitat. Yes, it is in space, not a great environment, but you are assembling fairly simple components (presumably using robots), then rotating as you build to 1g (with such weight, acceleration would be very slow, but that does not matter). A 30% markup on raw material costs should suffice, given that the latter a are fairly high. Then I have added 200K per inhabitant to cover installed capital such as housing, living infrastructure, power through solar cells etc. – essentially US value of capital per person less the value of land.

Previous chapter:

How much does it cost?

Next chapter:

Costs per head are acceptable, at high density