First Step: Cost Effective Launch

The biggest single problem is escaping Earth’s gravity at reasonable cost. To get to low Earth orbit you need to travel at 28,600 kms/hour, and 50% faster to escape the Earth’s gravity completely. So far we have used rockets, which means that virtually all the energy at lift off is for transporting the fuel (payload is only around 4% of total weight) and its casings/engines – and then it’s thrown away after a single use. Imagine building a Jumbo jet and using it only once - fares would be high…

Back in the days of the Apollo programme a Saturn V rocket would cost over $20,000 (in today’s dollars) per kilo to LEO. Space X have led the drive to lower costs, and a Falcon Heavy launch to LEO would cost around $2000/kg at present. Space X have successfully managed to recover all three stages of a Falcon Heavy and reckon it can be reused up to 10 times. The next Space X project is the Super Heavy, which can carry a 100 ton payload. It’s designed to launch a return mission to Mars, which I consider the wrong objective as described later in this blog, but the key factor is the very low costs claimed to Earth orbit due to:

- low construction costs

- cheap fuel (LNG instead of hydrogen)

- full reusability for 100 launches or more

- efficient engines. Space X owner Elon Musk claims that cost of launch to LEO would be $70/kg, and operating costs of only $20/kg. This is a startling claim as it is an order of magnitude lower than existing rockets, and needs verification. If true it would be a game changer, however.

There is however another major objection to rockets, for transporting more than a few astronauts. They are dangerous - there is an average 2% failure rate for launches, including for Space X, with a strong likelihood that all human passengers would be killed. That is an unacceptable level of risk for mass transport. By comparison, even in days of piston engines (more unreliable than jets) civil aviation accidents did not exceed 0.004% of flights:

There is a huge volume of rocket fuel and if there is a fault the mixture is literally explosive - liquid hydrogen in particular is difficult to handle, as the melting point is close to absolute zero. Commercial airliners full of fuel are potentially flying Molotov cocktails, however, yet are very safe. The difference is that commercial airliners serve a large mature market, new models are rigorously tested before being introduced into service, and manufacture benefits from a long experience curve. The small volume and expendable nature of space rockets to date means that neither consideration is true in this case.

TheSkylon concept uses air breathing ramjets for part of the way, and will be (if built and if it works) a true space plane rather than a multistage rocket. The key part is a new design of ramjet engine:

The engine’s secret is its heat-exchanger technology that can can cool air entering it from 1,000°C to minus 150°C in just one hundredth of a second whilst preventing ice from forming within the unit. This allows the engine to switch in flight from air-breathing mode at Mach 5.5—twice as fast as a jet—to that of a rocket engine, reaching Mach 25, or 7.5 km per second.

Even this proposed vehicle has propellant for 80% of its weight, and the payload is only 5% of the vehicle weight – and that is only to low earth orbit. Moreover Skylon (image below) would cost over $1 billion to develop – as much as a major airliner, but without the volume of sales to recoup the cost.

Source: http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/science-environment-27591432

Source: http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/science-environment-27591432

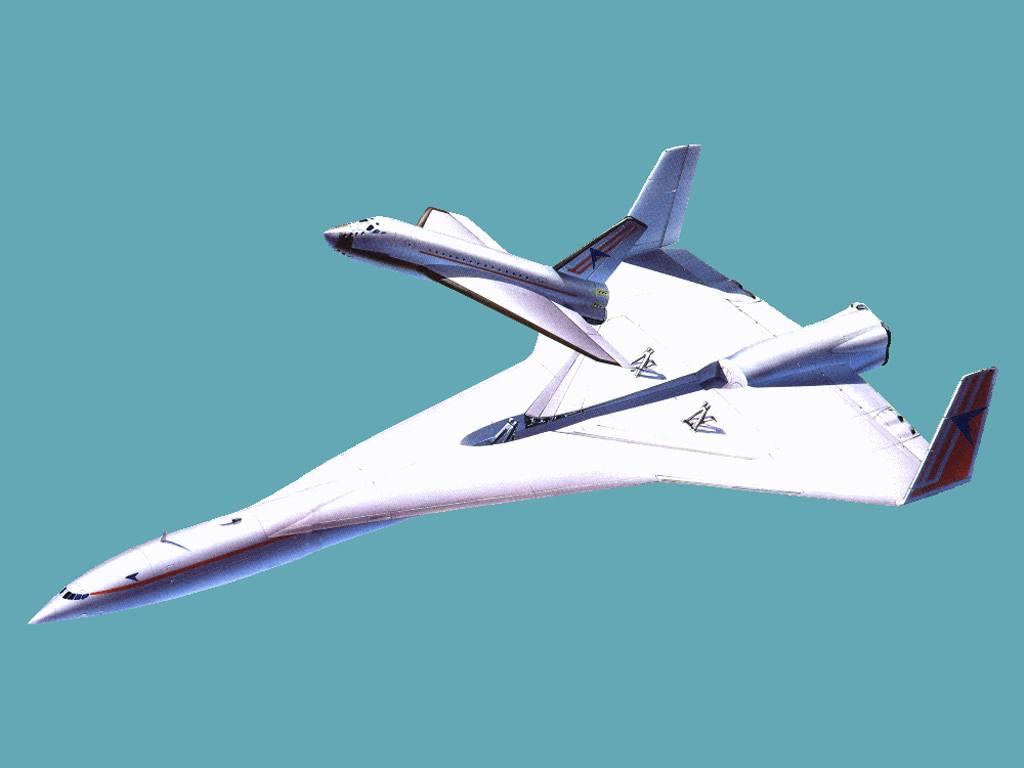

The economics of fully reusable space planes might be improved considerably with a two stage version. Bristol Spaceplane’s Spacebus proposal would have a first stage which would go up to Mach 4 with ramjets, then to Mach 6 with rockets, then release the second stage which would go to orbital velocity. A two stage space plane was the original plan for the space shuttle, a missed opportunity because of budget cuts, but it would be more efficient now with improved ramjet designs.

Source: http://bristolspaceplanes.com/projects/spacebus/

Source: http://bristolspaceplanes.com/projects/spacebus/

Environmentally, burning hydrogen and oxygen only produces water, the issue is how the hydrogen is produced. At present is currently made from natural gas, and thus does create carbon emissions, but the price of solar power is falling so fast that electrolysing water to produce hydrogen and oxygen may soon be cheaper and carbon free. As for ramjets or LNG fuel, as with all aviation, one can only hope for the development of carbon neutral biofuels.

Previous chapter:

Space Habitats Revisited

Next chapter:

Alternatives to Rockets: Space Elevators, Launch Loops, Startram