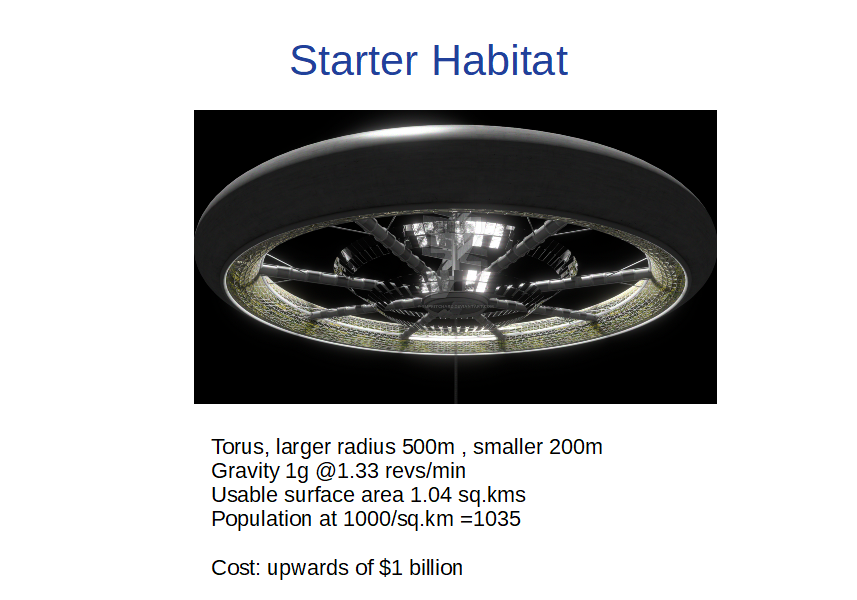

Getting Started: A Starter Habitat

So, in the long run, one could build habitats for around the cost of real estate in the big city, and one could get there for the cost of an intercontinental flight. So colonising space is economically viable. The problem is how to get to that stage.

OK, let’s see if we could start with a much smaller habitat, but still big enough to grow its food. around 1,000 people. I have assumed a single torus with a larger radius of 500 metres, an inner radius (to the torus itself)of 200 metres, and that half the internal area of the torus is habitable.

If we use the same input costs as for the larger habitat in the previous section, total construction costs come to around $1 billion. However this is totally unrealistic. Parts for the first habitat will include sophisticated engineering which will take time to develop in space.

What if, however, the raw materials and parts are transported from Earth, instead of assembled in space? It can do without soil (only hydroponic agriculture). Perhaps (with difficulty) with space planes assisted by skyhooks we can get launch costs down to $100/kg. Then the starter habitat costs $188 billion. However Startram claim that they could get launch costs down to $43/kg which would give a cost of $84 billion for the habitat. Startram is estimated to cost $60 billion, but it is still cheaper to build it (including future use) than relying on cheaper capital cost but more expensive launch cost options.

Note that cumulative costs (launch, assembly, maintenance) of the International Space Station is over $100 billion to date – and that only weighs 420 tons, and the living area is barely the size of a suburban house.

Habitat Location

It is tempting to put habitats in LEO, where under the protection of the Van Allen Belts an artificial magnetic field to protect from radiation would not be required. There are two problems, however.

The first is that it would spiral back towards Earth, although very slowly.

A more important problem is space junk. There are half a million objects circling this planet already, satellites have already been destroyed by collisions, and the problem is getting worse. Even a small habitat would be a much bigger target than a satellite.

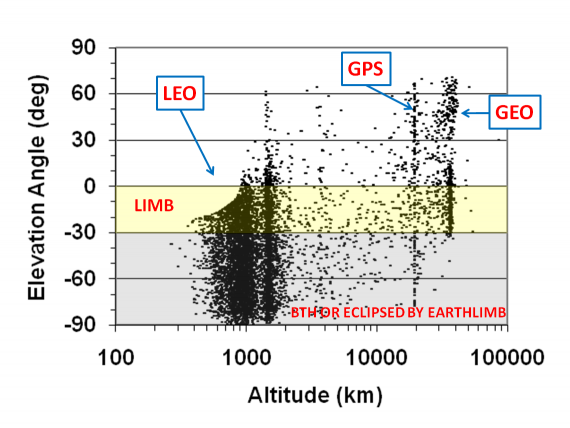

The chart below shows the current distribution of objects in space.

Source: aer.com

Source: aer.com

Most are clustered in the 7000-20,000 kms from earth range, within the protection of the outer Van Allen belt, but high enough to have long lived orbits; even so, the higher objects will spiral down over time. There is a smaller cluster at or just below 36,000 kms which is geostationary orbit, but they are exposed to more radiation (within the range of the outer Van Allen belt).

As long as radiation protection can be assured (see previous posts) then habitats are best placed beyond 36,000 kms to avoid the space junk problem, and will need to take measures to ensure that they don’t create their own space junk.

Nevertheless it makes sense to build the first habitat at LEO. That way launch from Earth requires a lower velocity than into deep space. Human passengers would transfer to a deep space vehicle which would not need to be as powerful, and could rotate to provide artificial gravity. If a Startram type launcher is used from Earth, goods destined for deep space could be accelerated at faster then 3g in unmanned vehicles so making the trip in one go.

When larger habitats are built, the starter habitat could then become purely a transit station.

Previous chapter:

Costs per head are acceptable, at high density

Next chapter:

What would motivate the development of space colonies?